Untrashing a TRS-80

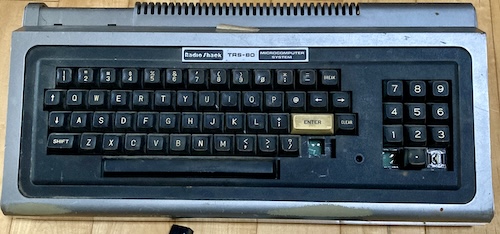

This Model 1 TRS-80 has been through a lot before it was rescued out of an e-waste dumpster by my friend. With some patient work, I should be able to turn it back into a computer. But how bad will this Frankenstein’s monster of a trash 80 become in the process?

What do we have?

Tandy was one of the first to the personal computer game. The TRS-80 is a Z80-based home computer from the late 70s, and they sold a lot of these things.

Most Model 1s you’ll encounter have an “expansion interface” attached, which is a large flat box containing extra RAM and some peripherals (most importantly, the floppy controller.) This computer came with a cable attached to the expansion connector, but no expansion interface on the other end of that cable, so either it was lost in the bottom of the ewaste dumpster or was cruelly separated from it. That’s too bad, but it does give me another project in the future if I end up liking this thing.

Since this machine had been inside an e-waste dumpster for awhile, it had been basically rock-tumblered with everything else in the box. That caused a lot of case damage, but it also broke some other, more valuable bits. Shaking it out, I found:

- Key caps;

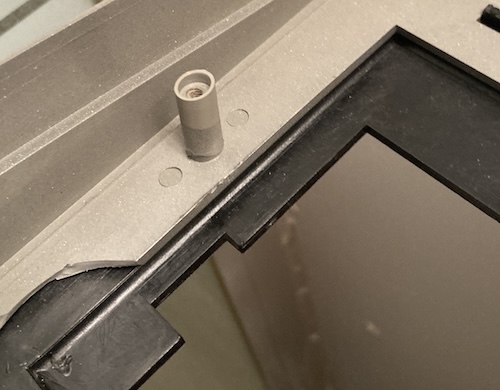

- The power LED and its retaining gasket;

- Broken pieces of what seemed to be a key switch;

- An SMD fuse holder(???);

- Random pieces of conductive foil

Oh yeah. This is going to be a project.

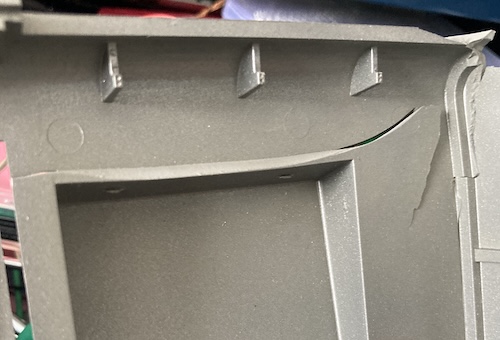

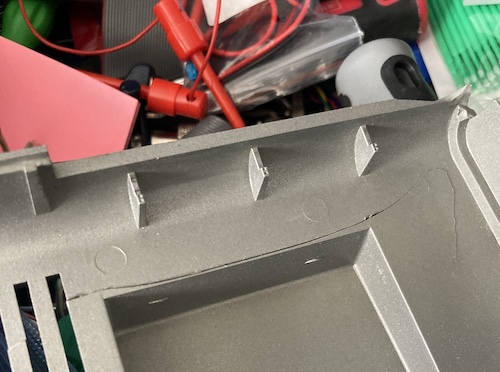

This poor computer’s top case was broken in two spots, with a big crack in the corner that had folded the case over itself. There was also a smaller crack across the expansion port frame, and the expansion port cover flap was missing entirely.

The port cover with labels had fallen out, so I had no idea which of the three identical 5-pin DINs were which!

You don’t want to mix these up, because one of them is power, and can serve around 20VDC and 20VAC. I would assume the tape logic and video output do not appreciate this. Plus, the power supply brick doesn’t even have a switch on it, so one accidental mis-plug even with the system off will cause damage. Hey, it was the 70s. If you weren’t paying one hundred percent attention while plugging things in every single time, clearly you just aren’t cut out for this brave new future of being asked about MEM SIZE?

A whole corner of the bottom case is missing, so making it nice is not a priority. Not able to find my usual quick-setting model cement, I instead used Tamiya Extra Thin model cement to first bond the big crack and then the smaller crack while squeezing them together by hand. The cement seemed to melt some of the silver paint, so be careful with squish-out.

Everything seemed more torsionally rigid after doing the very basics of case repair, which meant I was going in the right direction, and it wasn’t likely to just explode again like an Apple case.

The top case has this black keyboard-surround insert. That insert is cracked so badly in the corner that someone has run a self-tapping screw in here to replace a missing tab and hold it in place. This supports the theory that the machine was damaged way before it hit the recycler, because only someone who wanted to keep using the computer would care enough to do something like this. Probably it got dropped or smashed when it was still in use!

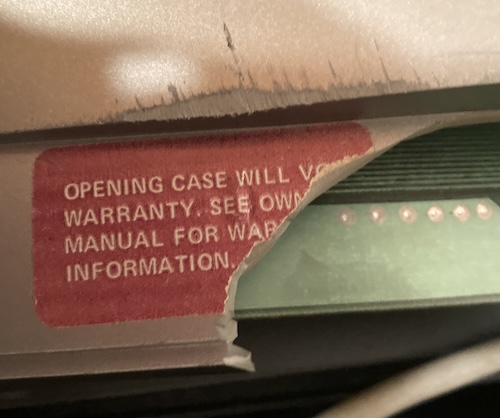

Think my warranty is still valid? I didn’t open the case myself.

Case Repair 101

Every single screw post on the top case was broken off. I removed them one at a time and marked where they came from.

Removing the screw posts from the screws took a lot of effort, but once it was done, I was also able to take a look at this giant dent on the back case. Some gentle heat and prying made this finally pop back straight after about ten minutes of work:

I had a lot of trouble getting the model cement into the cracks of the case. An additional problem is that my clamps really did not like to seat on the curvy TRS-80 case, so it was hard to hold things together while they dried.

In some places, I stitched the ends together with a soldering iron on very low temperature to help hold things together while it dried. The end result is not particularly pretty, but this was never going to be a full restoration with so many pieces missing. A better restoration would probably involve moulding new corners, or simply 3D-printing a whole new case. For now, I’ll be happy if it holds together well enough to be typed on.

When I had to reattach the broken-off posts to the top case, I first did a dry fit. Then I marked the orientation, applied a generous slathering of model glue to both sides, and put them back in place with the position markings lined up. This is much better than my usual tactic, which is to get both sides wet with glue and then forget exactly what orientation everything is in, then panic.

I also used way more cement than on previous projects, which I think made a big difference here. I’m reasonably happy with how I was able to restore the broken-off screw posts to the top case.

One of the posts was missing most of its guts, which made it impossible to repair. The remaining five will have to take on the brunt of the case load.

Since the back plate was missing, I went and found some pictures of other TRS-80s to figure out what is what. The power connector is, unsurprisingly, the one with the power switch next to it. The middle one is the composite video connector, and the outermost is “tape.”

I did order from JLC a new back plate to be printed based on the one in the aforementioned repository, and it showed up very quickly and looks great.

For that extra little smidge of safety, I also wrote with a Sharpie on the motherboard underneath the power port, indicating that it was indeed “power.”

Further inspection

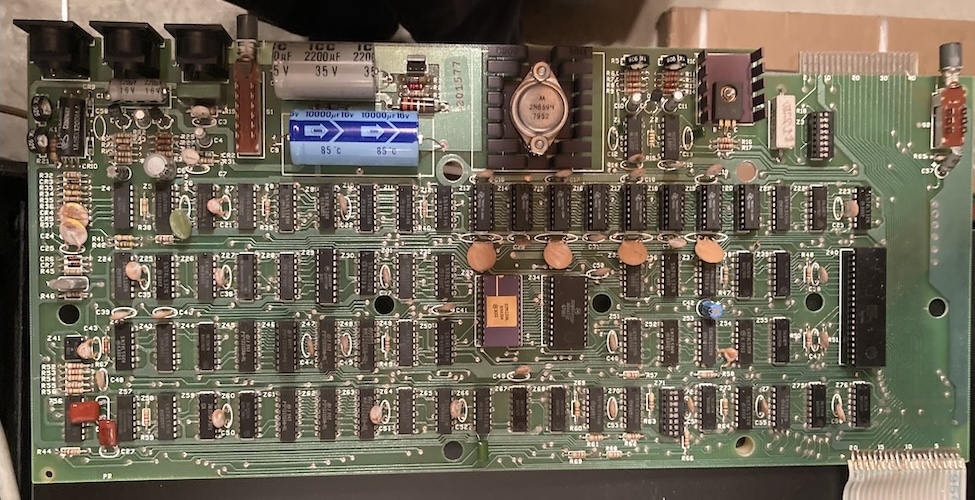

Despite everything this poor computer has been through, the motherboard looks like it’s in pretty good condition. Maybe all the dirt and dust that’s usually in these things fell out through the giant hole in the case.

Although the Model 1 is a very normal-looking Z80 system with no exotic custom chips, the age of the construction means that there’s still a lot of unusual-looking stuff going on with this board, especially in the power-supply section. I can absolutely see why a lot of people swap the RAM out and then do a 5V-only conversion. I’ve never owned a MOSTEK-made Z80 before, either: to be honest, I didn’t even know they made them before I opened this sucker up.

Looking forward to coming back here in order to understand how they make video. I have wanted to do a character generator for a long time now.

Power Supply

One of the sticking points on rebuilding this model 1 TRS-80 was figuring out what power supply to use. No power supply came with this system, and used ones are very expensive after shipping since they consist mostly of a giant heavy brick. I didn’t want to spend a bunch of money on a power supply only to find out it was broken, but I needed some kind of power supply to find out if it was broken. Think I read a book about this kind of problem once.

Like a lot of systems of its era, the TRS-80 needs split voltages to run the DRAM. Although it’s certainly possible to convert it to 5V-only RAM and run an internal regulator, it’s probably not the best diagnostic process to be modifying a system while also trying to repair it.

Instead, I looked around and found this PSU build guide from Shock Risk. It uses a commonly available Triad F-241U transformer (which outputs 18VAC and 9VAC.) Transformers are oddly expensive when bought in single quantity: this one cost an eyewatering $36.

The original TRS-80 PSU provides ~20VDC which is regulated to 12VDC inside the computer, and 17VAC for rectifying and regulating into +5VDC and -5VDC inside the computer. This is my first time wiring up a mains transformer, so I’m glad someone went ahead and did all the hard work of figuring how to do it. I’m also glad they included photos, because I did not have enough confidence in myself to go solely off of the schematic.

Rectification for the “you left me plugged in” LED and the DC rail is done on the PCB, which doubles as a mount for the transformer into the case. It’s pretty straightforward, and just uses a pair of high-wattage 1n4001s. It took me a little bit of experimentation from my screw collection to determine that the threaded inserts in the case were M3 screws; the case manufacturer only included the screws for the lid.

Following the guide, I also sourced an identical Bud enclosure, but I also made sure to get a “DAC-13F” fused IEC power connector. Having a fuse is a good idea!

This was absolutely not the most economical approach to getting power into the Model 1. Probably the easiest and cheapest way would have been a 5V conversion with 4164s, but the power supply is a solid build where someone else has already figured out most of the snags, which I’m super grateful for. Hopefully I get a lot of use out of the Model 1 to justify it!

As for the case, I had a really great plan to use my knockoff not-a-Dremel to cut the hole for the IEC connector, thus avoiding me having to hand-drill like on the second ADAM power supply. That plan didn’t last long, partially because the not-a-Dremel’s wheels are too small to get a good plunge into the thick plastic, but also because of my relative inexperience with the thing. Maybe I should’ve used an angle grinder… anyway, I ended up drilling holes around the periphery with a power drill, and then cutting it out this time. Much faster.

When wiring the transformer, I had a lot of trouble. Initially, I wanted to use some spade connectors that fit perfectly on the tabs of the transformer. When I actually wired everything up and went to test fit it, however, it turned out that the spades were too long to fit. I love doing the same job twice, but worse the second time around!

After a lot of annoying pushing and fondling to get everything into the case, including breaking the legs off the LED and having to put a new one in, I was finally able to tuck everything together.

Getting the M3 screws that mount the PCB down were a bit of a pain. It’s just deep enough to make the screw fall off the driver as I’m lowering it into the case, and whatever material they were made out of is simply not magnetic. I ended up putting a bit of sticky tack on the head of the hex key.

Similarly, I used RTV to hold in the LED and the IEC connector, but I had left it in the garage in December weather and didn’t take my time to warm it back up properly. Winter cold made it take a really long time to cure, and it was really difficult to get out of the tube so I put it on too thin. Like painting in the winter, I’d stick this in a cup of warm water first next time.

That RTV also didn’t do a great job sealing the connector, since its natural stretchiness let the connector move around a lot when the cord is being plugged and unplugged. Not a good combination for mains power. I will be using the screw holes, like I should have in the first place.

Overall, I feel like this power supply build went fairly well. If I had to do it again, I would be tempted to try the RetroStack TRS-80 Model 1 power supply, which uses a somewhat smaller transformer and a very nice 3D printed case.

I plugged in the supply and tested the AC and DC voltages unloaded – they were high, of course, but seemed to be in the range of what I needed. Now, it was time to go onto making another cable.

Video cable

Here’s a fun fact: when the Model 1 came out in ‘77, it was extremely uncommon for television sets to have composite video input ports (and still not super common for small sets, for most of a decade afterward.)

The Model 1 has no RF modulator, so how did they connect it to a monitor? Tandy modified a common television set to have a composite input, and sold it as the TRS-80’s special monitor. What they’d actually done is take a hot-chassis television set, and modify it, making the TRS-80 itself power the opto-isolator that sends risk-free composite video into the set.

What this means is that the TRS-80 provides a +5V output alongside a luminance-only composite output. We’ll skip that +5V output and wire the rest into a standard composite video cable.

Conveniently, the composite video cable for the TRS-80 Model 1 is also a five-pin DIN, so I just grabbed the other half of the 2m MIDI cable I chopped up and soldered a yellow male RCA connector to the other end. This doesn’t produce an extremely long video cable, but 1 meter should be enough to reach a monitor on a desk for now.

To provide a little bit of strain relief, and also keep the cut-off ends of the unused conductors from shorting to anything, I once again put a glob of RTV in there before sealing up the connector. Surely if I keep trying it, eventually things will work out for me and the stinky toothpaste.

Does it work?

I put the motherboard back in the (beaten up, but now somewhat stronger) bottom case and applied spacers where I felt like they should go. This is almost certainly not correct, as I remember some of the spacers were doubled up, and I ended up with leftover ones, but it is good enough for a precarious test.

Admittedly, this is not the most ESD-safe environment, but a TRS-80 Model 2 was clogging the entire desk at the time, so I had to do what I could. You get it.

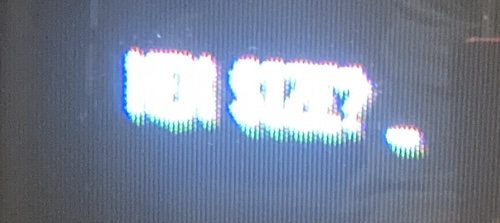

Surely, this completely battered computer won’t start properly. I bet I get a screen full of garbage or some kind of ominous screeching noise followed by smoke!

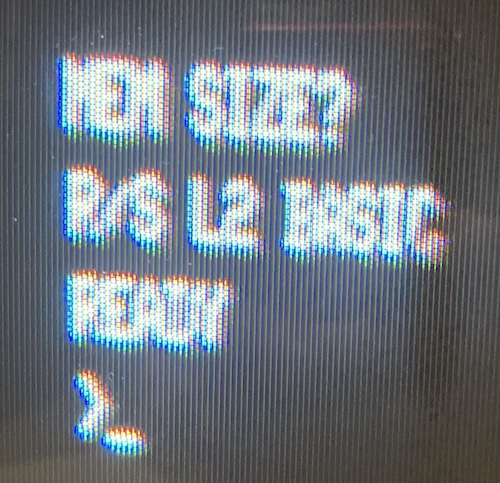

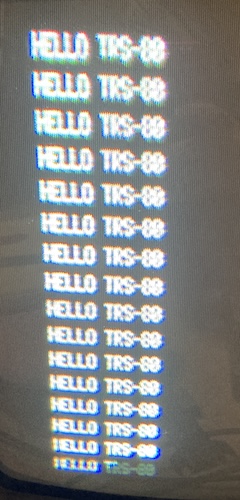

Oh. Well. Or it could just work. Maybe the keyboard is broken? I’ll hit enter.

Surely there has to be some problem with this that will keep me from entering a program.

A couple of the keys were pretty bad, but after some repeated pressing they came back to life. Frankly, I’m a little bit surprised: the ribbon joining the two boards didn’t look particularly good.

Dang. This computer might actually work. These things are tough.

Conclusion

This part of the project went really well. I had to build a lot of cables due to the TRS-80 Model 1’s pioneering nature, but it’s not like it was very complex stuff. I don’t mind a project that’s time consuming and productive; the ones where it’s time consuming and you never seem to make any progress are much more discouraging.

From doing the power supply, I learned a little bit about how to wire a transformer. I think now I would be much more confident debugging a linear power supply, or even building one for an oddball voltage. Maybe a Commodore 5VDC/9VAC one could be my next stop.

From building the composite video cable, I learned basically nothing, but I think it looks a lot nicer than my average cable. Starting with a pre-soldered DIN cable here (the MIDI cable) helped a whole lot, even if it is annoyingly short.

Case repair is always a bit of a crap-shoot. I’m glad I was able to find my quick-setting Tamiya, though it seems while I was working on this, the old-computer community started getting really interested in UV resin. Paired with some screen-door mesh, that might be a good way to reinforce the top case against future damage, although the giant holes will still remain.

Cracks aside, I’m not sure how much further I want to go with repairing the big holes in this old case. I could mould some new corners with packing tape and epoxy, or I could simply spend forty bucks and get a new one printed.

My next step will be working on that keyboard, and getting everything to look nice with the top case installed. I suspect I’ll want to start with figuring out how to solder the power LED back onto the motherboard: I wasn’t able to immediately guess the polarity with a continuity test to a known ground and +5V, but I can always poke around with a longer-legged LED to see which way it lights up.

Then, it might be nice to load some actual software on this sucker. I’ll need another 5-pin DIN…

Thanks for reading.

Repair Summary

| Fault | Remedy | Caveats |

|---|---|---|

| Top case is shattered. | Fix broken posts with model cement | Unlikely to be a good long-term fix; screws will probably break it again as the plastic continues to shrink and embrittle. |

| Bottom case is shattered. | Bend cracked parts straight by hand, and then glue with model cement. Reinforce with soldering iron. | A big chunk of the case is still missing. |

| Port label backplate is missing. | Print a new one. | |

| No power supply was provided. | Build one. | This power supply is big and heavy and kind of inconvenient to store, but it does work really well. |

| Power LED is broken off. | Not fixed at this time. | |

| Several keys are broken off, and many key-switches are damaged. | Not fixed at this time. |